The baffling riddle of the face at the porthole

New light on a weird, glamorous enigma of crime

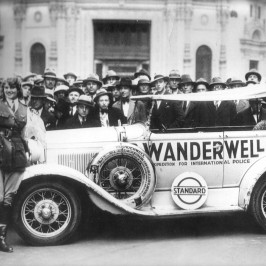

Aloha Wanderwell! What a name! What a girl! Not that I ever saw her, or she me. And not that it would have made any difference—me being a worn-out old flatfoot from the New York Homicide Squad, and she being one of those round-the-world glamour girls. But we won’t go into that now. We will, however, go into the West Coast’s most baffling crime, the mysterious murder of Aloha’s mysterious young husband on the mysterious yacht Carma.

You remember the headlines: Globe Girdler Slain on Yacht in Sea Intrigue; Duke of Manchester’s Son Among Crew; Cowardly Murder of Captain Walter Wanderwell, Suspected Spy, Untiring Seeker after the Bizarre in Life; Beautiful Young Wife Missing, etc., etc.

The murder itself was simple enough. At least, it seemed so—at first.

There was something wrong with the lighting system of the Carma on the night of December 5, 1932. The old two-master was tied up to a deserted pier on the Long Beach water front. Only one light, a flickering one from an oil lamp, struggled faintly through the porthole of a cabin on the starboard side.

Any one bothering to look through that porthole would have seen two very pretty young girls writing letters; two good-looking young men chatting. Presently, about nine o‘clock, somebody did bother. The face of a smooth shaven young man suddenly appeared out of the darkness and framed itself in the porthole.

“Where is Captain Wanderwell?” asked the voice of the face.

On being told that the captain had just gone forward to his quarters, the face disappeared. Five minutes later there was a loud report. The two men rushed from the lighted cabin. Nothing was to be heard or seen. Groping their way forward, they found the leader of their expedition – the Little Admiral, as they called him— doubled up on the floor of his quarters, his head against the wall, a bullet hole between the shoulders, dead.

But what had become of the man at the porthole? Was there any such person? Who were these young men and women—the latter more suitable for a Ziegfeld front row than for a ship’s crew.

Had they told the true story of what happened that night on the yacht Carma? Had one of them killed Captain Wanderwell? And what was the Duke of Manchester’s son doing in such a mess?

Lord Edward Eugene Fernando Montaguson of His Grace the Duke of Manchester and the latter’s immensely wealthy wife, the former Helena Zimmerman of Cincinnati, told a straightforward story. He was a remittance man, whose business in life was wandering over the world in search of adventure. That’s how he happened to sign up as an ordinary seaman on the Carma.

“Where was the yacht Carma going?” asked Police Lieutenant Miller of the Long Beach night watch. “To the South Seas.” “What for?” “For the World International Police.” “What‘s that?” “The Cap didn’t say. You’ll have to ask Aloha…”Well, here was Mystery with a capital M. World International Police indeed! Who was this Captain Walter Wanderwell who chartered leaky old yachts and had dukes’ sons and ravishing young beauties for his crew?

It was clear that neither this question, nor any of the others which immediately came to the lips of police and newspapermen, would be answered until Aloha told her story. And Aloha wasn’t there to tell it.

Beautiful Aloha—blonde, curly-locked, and alluringly feminine, who had met the Little Admiral—of all places! — outside a movie theater stage door in Nice. She was one of those expatriated children getting a cultural education on the French Riviera. On her way home from school, she saw the Cap’s picture outside the little Franco-American theater, where he was making a personal appearance along with the films of some of his earlier travels. His name was known to her in a vague way as a celebrity, and his photograph was certainly “swell.” So in she went. And after the show she waited for her new crush.

They walked home together. He told her he was looking for a secretary, and preferred one who could sing a song or two in his movie act. Aloha got the job. She was only sixteen at the time, so her mother insisted on her becoming the captain’s ward. To make things doubly sure, mother also adopted Wanderwell as her son.

“Technically,” explained Aloha, “he became my brother.” This mere technicality, however, did not prevent Aloha—after three years of secretarying, which included a motor trip around the world, from marrying her employer, guardian, and “brother” in Riverside, California, in 1925.

Thereafter, for seven years, they continued to live a life brimful of romance and adventure, which started with a honeymoon trip through France, Spain, Switzerland, Germany, Poland, and thence across Asia to Peking. Trips to Africa and South America followed. Always it would be the same technique: the captain would advertise for young men and women who wanted to see the world, charge them about $200 for the privilege, and work them hard taking films, selling pamphlets, and appearing in theaters—all for the World International Police.

0n the latter subject Aloha was almost as vague as Lord Eddie had been. It was, she said, the Caps “pet scheme to do his bit for universal peace.” And all the boys and girls who signed up with him had to do their bit too, not only for universal peace but for the support of the expedition. The boys were invariably young and adventurous, the girls young and pretty.

“But there was never any immorality in our party,” insisted Mrs. Wanderwell. “Cap was always quite strict about contacts and relationships between men and women on our expeditions.”

About the trip they were planning at the time of the tragedy, Aloha said it was like the rest, except that it was to be in the Wanderwells’ own boat.

“Cap had always talked of owning a ship,” explained his widow.

According to his custom, Captain Wanderwell had advertised for “crew and cooperative passengers,” and had received replies from all over the world. Eight girls and seven men had already signed up, and were either on the boat the night of the murder, or in the town arranging for the journey.

The four who were in the lighted cabin when the face appeared at the porthole were Cuthbert Wills, an Englishman, who was to act as engineer of the schooner’s 120 horsepower supplementary engine; Mary Parks, a student from Boston; Marian Smith, youngest of the lot, from Georgia; and Edmund Zarenski, a cameraman from Delaware.

The mystery of Aloha Wanderwell’s own whereabouts on the fatal night was partly cleared up when she was found occupying a rented room with her sister in Hollywood, where, so she said, she had gone to complete a sound track for one of Captain Wanderwell’s films.

Faced with the news of her husband’s tragic death, she showed none of the signs of a widow broken with grief.

“Where are my children?” she asked quickly. As a matter of fact, Valry, aged seven, and Nile, aged six, had slept right through the shooting which had caused the death of their father.

On being told that her children were safe in the care of a police matron, their young mother, usually a soft, smiling, joyous creature, lapsed into that state of glittery immobility which was to earn her the name of “the Rhinestone Widow.”

To the Long Beach police she became the case’s biggest question mark. Had she absented herself from the Carma the night of December 5 on a legitimate errand? Or had she known that a tragedy was to take place on the ship that night, and run away to save herself from being suspected as the slayer? What was the real relationship between this man and this woman? Did she love her husband? Or was there someone else? And was that someone else the man at the porthole?

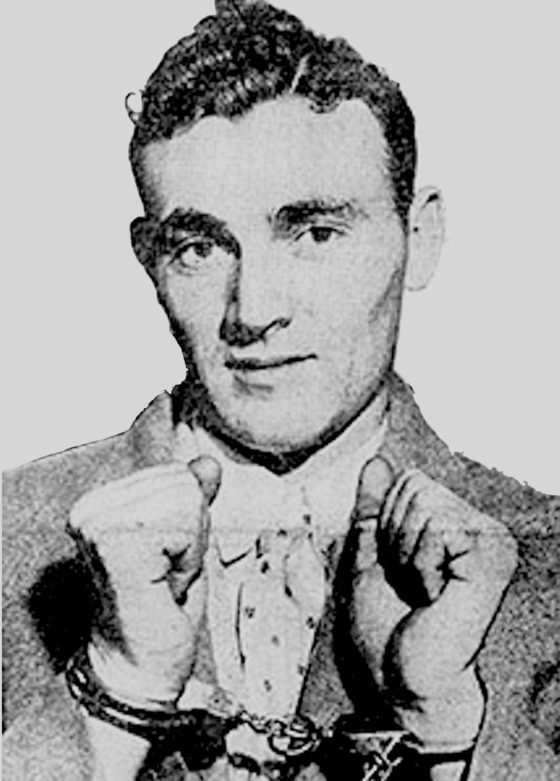

While Lieutenant Miller and Lieutenant of Detectives Owen Murphy of the Long Beach police force were pondering these questions, a personable young man with curly black hair and an ingratiating smile, a guest in the Glendale home of Aviator Eddie De Larm, opened his morning paper and read with apparently casual interest the news of the day. A few minutes later he rose from his chair by the fireplace, announced— in an accent that suggested Australia— that he had “mooched” on his good friends the De Larms longer than he should, packed his bag, and departed for a vague destination known as “the country.”

Eddie De Larm, an American Indian by birth but who looked more like a Cuban or an Argentinian, was not surprised at his friend’s action. He also had read the papers. He knew that the man his curly haired friend hated most in all the world was dead—with a bullet hole in his back.

De Larm had known the boy for several years. Met him first in South America. His wife liked him. So did his two daughters, sixteen-year-old Betty and thirteen-year-old Juanita. They had enjoyed having him in the house. They were his pals. De Larm said nothing.

Meanwhile the detectives were pounding at Aloha. Surely the captain must have had enemies. By this time they had found out that Walter Wanderwell was really Valarian Johannes Tieczynski, who had served a term at Atlanta during the war as a suspected German spy; and that he wasn’t a captain at all, but had only recently paid a fine for the unauthorized wearing of a United States army uniform. Such a man might well have alienated, perhaps cheated, a friend.

“No,” said Aloha quite dispassionately. “Cap might contrive little schemes to gain some particular end when no one would be injured, but fundamentally he was the soul of honor.”

The boys were about to give up on her when she cried: “Wait! There was a man who caused us a lot of trouble. He incited members of our last expedition to mutiny. That was down in South America. And last summer he came to see my husband and demanded money.”

The detectives reached for pencils and pads. “And his name?” “I don‘t know. I can’t think what it was. Sometimes he was called ‘Curly’ and sometimes ‘Guy.’ I haven’t any idea what his last name was.”

Questioned as to where this “Curly” or “Guy” might be found, she professed to have not the slightest idea. All she knew of the interview the previous July was that her husband had told her the man had threatened him and had gone away saying: “I’ll see you again, Wanderwell, some time, some place!”

0n the appearance of the man she was more definite. He was twenty-six to thirty years old, medium build, five feet nine or ten in height, very curly hair. Later she dug up a group photograph which included a smiling young man of just this description. She also said that she knew he was on friendly terms with one Eugene Babbitt, an ensign in the Naval Reserve, and a man named Burenzeyski, a cook, both of Seattle, because he had persuaded both of them not to sign up for the present trip.

There wasn’t much to go on here. It was scarcely likely that a man of this Curly’s obviously happy-go-lucky type would have followed another man from Buenos Aires to Los Angeles to kill him on account of a mere disagreement. And if his object was money—well, there was over $600 in the captain’s pockets when the body was found.

The police communicated at once with the Seattle authorities, and asked them to locate, if possible, Babbitt and Burenzeyski. They also enlarged the picture of the young man in Aloha’s group photograph and gave it to the newspapers. Then they went back to work on what seemed like hotter trails.

Several torrid tips came from anonymous sources. Most of these were from people who purported to know fathers of young girls who had been lured away from home by Captain Wanderwell to take part in his expeditions. These parents, according to the letters received, were on the hunt for the Cap with eyes flashing and pistols cocked.

Not one of these statements proved to be true. They had probably been inspired by newspaper accounts of the youth and beauty aboard the Carma.

More intriguing to the police than these so-called clues was the problem of the missing murder gun. The captain had been shot with a .38-caliber automatic. The bullet, which had entered his back, was found protruding from his chest. The revolver, however, had disappeared as completely as the man who used it. The boys on the Long Beach force did all they could. They searched the boat and the dock and the street approaches on every side. They sent divers down to scan the sea bottom. And naturally, they questioned repeatedly every member of the expedition.

It was one of these, Eugenia Nabel, who gave them their first clue as to the identity—although not to the whereabouts—of the murder weapon.

“There‘s something I forgot,” said the girl. “Just a few days ago the captain told us that a .38 automatic had been stolen from one of his suitcases. He asked us to hunt for it in the downtown pawnshops. We looked in several, but since the captain didn’t know the number of the gun, we never found it.”

Here was a lead. That gun must have been stolen by someone who knew that the Cap had it in that particular suitcase. Nothing else was stolen. Who would have known? Aloha, naturally, since she was the only person who might properly have access to the captain’s belongings.

Had Aloha Wanderwell taken her husband‘s revolver and given it to his murderer? Had the captain been shot with his own gun?

The police had to admit that there wasn’t any evidence to support the first assumption. There was, however, a strong probability that the second was true.

Who else, besides Aloha, could have stolen that gun and not been detected?

Obviously no one except one of the boys and girls of the crew, for the Carma was never left without at least one of them on board. Back over the alibis of these fifteen youngsters went Lieutenant Murphy and his experts. Some of them had been selling pamphlets in the streets that evening. Others had been making personal appearances with the captain’s films. Others had been doing advertising stunts for tradesmen, to pay for supplies. All had witnesses to substantiate their stories.

Moreover, each and every one of them had successfully passed the paraffin hand test, which would have disclosed which of them, if any, had recently discharged a gun- unless, of course, he had worn gloves. And it did seem rather farfetched to think that any one of these youngsters was so versed in the science of crime detection as to take that precaution.

Finally, in desperation, Murphy and his men turned back to the clue of the boy who was sometimes called “Curly” and sometimes “Guy.” The Seattle police had located the naval ensign Babbitt. He admitted that he had been present in Wanderwell’s apartment in the Hotel Arcady in Los Angeles one evening last July, when Guy, accompanied by a dark man who said he was an aviator, had called to demand the money which he claimed he had deposited with the captain.

This brief news item, hidden away in the mass of pictures and special stories of the tragedy which the papers were running, caught the watchful eye of Carlton Williams, star reporter of the Los Angeles Times, as he was sitting in the waiting room at Los Angeles Police Headquarters waiting for Detective Joe Filkas.

Trained by long experience in murder cases, Williams knew at once that here was the clue which should ultimately lead to the apprehension of the man Guy. Filkas agreed with him. Together they went up to the Arcady, a fashionable apartment hotel on Wilshire Boulevard.

Manager Bristol remembered the row of the previous summer. Well he might, for he had been roused from his pleasurable contemplation of the day’s receipts by a man’s voice crying: “Help! Police! I’m being murdered!”

Rushing into the street in search of the supposed bandits, he observed Wanderwell leaning far out of his window and yelling for help. In the captain’s room he found Babbitt, who was staying with Wanderwell at the time; the curly-haired young chap whom the captain addressed as Guy; and a somewhat older man, apparently a close friend of Guy, who looked like a Cuban or South American and said he lived in Glendale. They got the name, De Larm, at a nearby airport, and a man who could lead them to him.

De Larm, a decent chap, was soon convinced that it was his duty as a citizen and as a friend to help find Curly Guy—William James Guy was his full name—and bring him back to prove his innocence. De Larm had a shrewd suspicion as to where Guy was hiding; and it proved correct— an unlighted frame house on an unpaved street down on the river front.

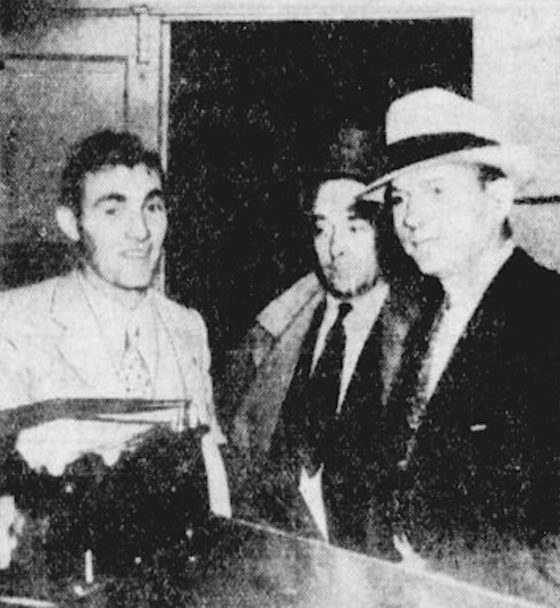

With only one gun between them, and no flashlight, Filkas and Williams rushed into the darkness of the house, wakened its lonely occupant, and informed him that he was under arrest.

To their great surprise, they found the likable curly haired boy rather glad to see them. “If you hadn’t come,” he said with his slight accent, “I think I would have given myself up anyhow. The only reason I‘m hiding here is that I’m an alien and in this country illegally. Of course, a lot of people know I didn’t like Wanderwell, and that‘s one reason I didn’t want to be picked up as a suspect. The real reason, though, is that I didn’t want to be deported.”

Filkas and Williams made no comment. They noticed, though, that the neat gray suit and light overcoat into which the rangy young man climbed, corresponded in all details to the costume worn by the man on the boat, as described by Cuthbert Wills, the Englishman who had directed him to Wanderwell’s quarters. And the accent! They remembered now that all four of the occupants of the lighted cabin had spoken of a slight accent. “Colonial surely,” Wills had said; “possibly Australian.”

Guy made no secret of his feeling against the dead man. He and his wife, Vera, had read the Wanderwell advertisements in a Buenos Aires newspaper, for women who spoke Spanish and English. His wife, to whom he had been married only three months, and a girlfriend knew both languages, so they went with Guy to see the captain, who said they would have to put up $200 to go on the trip. Guy had $150, which he turned over to Wanderwell, who permitted the two girls to join the outfit. Guy remained behind until he had earned the other $50, then joined the party at Jujuy.

“I didn’t like Wanderwell from the beginning,” he said with disarming frankness. “He was a disagreeable and petty man, a regular dictator. Liked to be called the Little Admiral— all that sort of thing! He worked us like dogs. We were fed principally on beans.”

Conditions finally became so unbearable that I went to Wanderwell and protested. He regarded this as mutiny, and ordered the ship to dock at Colon. There he virtually put us on the beach—my wife, the other woman, and me. We were absolutely stranded—no money to get anywhere. Finally I arranged for a steamship company to take the two girls back to England, which was the address on their passports, and I set out on foot for Nicaragua. I haven’t seen my wife since— and I haven’t seen the money I gave Wanderwell.

“Vera was beautiful,” he continued, his voice softening, “and she must be now—beautiful enough to support herself as an artist’s model, and that’s something!”

As he spoke, he pointed to a clipping from a London paper about a prize which had just been awarded by the Royal Society of Portrait Painters to a canvas by the famous artist, Alexander Christie, for which the well known model, Vera Guy, had posed. Underneath the painting was the title, Solveig, the Young Amazon. Her, husband was right. Vera was beautiful.

Curly then rummaged in his pockets and produced a letter, which with justifiable pride he handed to his accusers. The letter read: Dearest “Biggie”: I am praying for the time to come when we can be together again… Have you still that big smile of yours? Keep it going in spite of everything. I love you. Vera.

Biggie still had the big smile, all right. Carl Williams and Joe Filkas had to admit that the man’s personality was distinctly likable, his story distinctly likely. Yet they knew that with every word he was driving one more nail into the scaffold on which he almost surely would hang.

For, at last, a motive had been uncovered. Wanderwell had not only robbed Guy of his hard-earned savings but he had robbed him of his bride of three months. Greater men than Curly Guy had committed murder for lesser reasons.

It was no surprise to any one when he was indicted for the slaying of Valarian Johannes Tieczynski, alias Walter Wanderwell.

Yet after listening to the testimony of Curly Guy’s loyal friends — Mr. and Mrs. Eddie De Larm and their pretty daughters, Betty and Juanita— that they were all sitting and talking with the accused in the De Larm living room at the very time the murder was being committed, and after watching for several days the smiling face and confident demeanor of William James “Curly” Guy, a jury of nine men and three women decided to disregard the absolute identification of Marian Smith and Cuthbert Wills, and bring in a verdict of “Not guilty.”

So Curly Guy went back to the welcoming arms of Solveig, the Young Amazon; the yacht Carma became a showboat, with admission for the curious at so much per head. And Aloha Wanderwell— what of her?

Well, at last accounts, she was still “carrying on” for the World International Police!

— AUTHOR NOTES ABOUT WANDERWELL MURDER —

It is not for me, a tenderfoot from the East, to criticize the police of Long Beach. It was a big case for a little department, and they did what they could with it.

The only important thing they seem to have overlooked was a secret passage out of the captain’s quarters into the hold of the vessel, where the man at the porthole might have secreted himself during the first search of the cabins and decks— or where somebody other than the porthole man might have lain in wait for the captain and killed him after the visitor had gone.

The important thing about this case to me is the emphasis it places on the difficulty under our jury system of convicting a really personable prisoner of the crime of first-degree murder.

Where would you find twelve men and women who would have convicted this good-looking young chap with the curly hair and friendly eyes and ingratiating smile of shooting a helpless victim in the back?